“The land of the free and the home of the brave”: the monument to Francis Geary at Great Bookham, Surrey

| Month: | October 2024 |

|---|---|

| Type: | Wall monument |

| Era: | 18th Century |

Visit this monument

St Nicholas

Church Rd, Great Bookham, Leatherhead KT23 3PG

| Month: | October 2024 |

|---|---|

| Type: | Wall monument |

| Era: | 18th Century |

St Nicholas

Church Rd, Great Bookham, Leatherhead KT23 3PG

Family monument to a young English cornet killed during the American War of Independence

On 14 December 1776 Captain John Schenck, leader of the militiamen in Amwell Township, New Jersey, set up an ambush for a British army detachment riding to Flemington on reconnaissance. The ambush was successful, the British driven off, and there was one casualty: Cornet Francis Geary of the 16th Light Dragoons, the leader of the detachment, a graduate of Balliol, the son of Admiral [Sir] Francis Geary of Polesden [Lacey], aged 24. The Americans unsportingly concealed Geary’s body, burying it in secret after spoiling it of uniform, sword and cap-badge (which would have had his name on it). This spiteful action may have had its roots in recent reports of atrocities, including the rape of girls and pregnant women, carried out by British and German soldiers in Hunterdon County, in which Amwell Township was situated, but Schenck, as a descendant of dispossessed Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam [New York] may have had personal reasons for animus against the British.

The ambush, known as the Ambush of Geary, or the Amwell Skirmish, was one of a number of militia operations in the area which forced the British to curtail their reconnaissance activities and confined them to a radius of about four miles from Trenton. This lack of wider intelligence meant that they did not find out about the Americans, led by George Washington, accumulating boats along the Pennsylvania bank of the River Delaware, to which Washington had been forced to withdraw in early December. Washington was therefore able to mount his surprise Christmas attack on Trenton (crossing the Delaware on the night of December 25 and engaging the British forces – Hessians – on December 26). The Battle of Trenton, while a small-scale engagement, is generally held to mark the beginning of the eventual American victory in the War of Independence (Fig 1: Map of the Trenton area, showing sites mentioned).

Francis Geary’s grieving parents erected a monument to him in St Nicholas, Great Bookham (Fig 2: Great Bookham Francis Geary†1776). Originally on the south wall of the chancel, it was moved in 1885 during William Butterfield’s campaign of restoration to its current position on the south wall of the nave[i]. It is executed in coloured marbles, the architectural elements in shades of grey, the representational in cream/bisque. A shield of arms with palms and garlands hangs from the top of the truncated pyramid that forms the main background, and on an elaborate frame is a composition in which Britannia sits rather uncomfortably on a heap of martial trophies, mourning over a medallion with a portrait-bust of Cornet Geary. On the apron is an inscription-tablet, reading

To the Memory of CORNET FRANCIS GEARY

(Eldest Son of Admiral GEARY)

Who fell in America December 13th 1776

By his Affability and Benevolence

he gained the Love of the Soldiers

And

By his Constant Attention to his Duty

The Esteem of his Superior Officers

At the Age of 24

He was Entrusted with a Command

Which he Executed with Singular Spirit

But on his return from that Duty

He was Attacked by a Large Body of Rebels

Who lay in wait for him in a Wood

And was Killed at the head of his Little Troop

Bravely Fighting

In Support of the Rights and Authority of his Country

In Testimony

of the Sincere Affection for a

Dutiful and much Lamented Son

This Monument was Erected by his

Most afflicted Parents

The most striking feature of the monument is the bas-relief depiction in the frame on which Britannia sits of the death of Francis Geary (Fig 3: Monument to Francis Geary detail). On the viewer’s left a road winds through a hilly and rocky landscape, a gate opening from it by some trees to a building with an arched entrance and a double-pitched roof. Some accounts describe the purpose of Geary’s expedition as to check that supplies of salt pork and beef for the troops were ready for collection[ii], so this may be a barn. In the centre a rough grassy area separates the road from fenced woodland, from which many American riflemen direct fire on Geary and his troop of five dragoons. A horse has already collapsed, and Geary, his sword falling from his hand, his plumed helmet blown into the air, his blood gushing from his head and splashing on the ground, collapses into the arms of the unhorsed dragoon (Fig 4: Monument to Francis Geary detail).

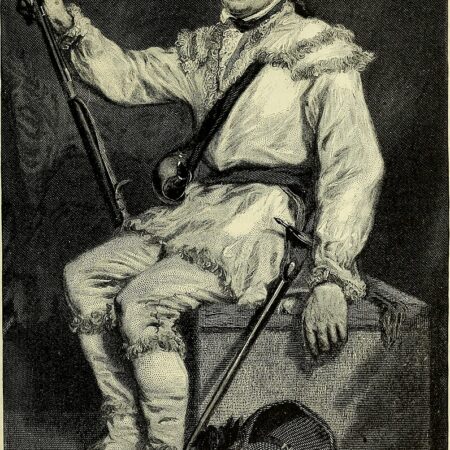

The only account of the incident comes from a kinsman of John Schenck[iii], and the relief substantially agrees with it, the major difference being that Schenck is supposed to have led a group of eight men, not the at least twenty-two shown on the monument: a numerical discrepancy that bears out the claim in the inscription that Geary “was Attacked by a Large Body of Rebels”…”at the head of his Little Troop”. Otherwise we see Geary losing his helmet and sword, which the Americans are known to have taken – the figure sneaking out through the fence at the bottom centre may be an American about to seize these spoils. The assailants are identified as riflemen both by their dress and their weapons. They wear the ‘rifleman’s frock’, a loose upper garment, which could be made of buckskin or (more usually) cloth, worn over trousers, both bearing fringes, which apparently made operations in bush easier[iv], and which may be seen in portraits of Daniel Morgan, the commander responsible for the tactical use of rifles during the American War of Independence (Fig 5: Image of Daniel Morgan in rifleman’s costume)[v]. They also use ‘long rifles’[vi], indicated by the fact that the American troops hold their weapons in a distinctive manner, one hand extended to steady the long barrel, as opposed to the dragoons who hold their muskets [possibly horse pistols] with both hands at the same point. The long rifle was a hunter’s weapon, ideal for use by snipers from ambush, with a range much greater than the musket used by the British. The British, understandably, felt that it was an unethical weapon[vii], but even George Washington seems to have had doubts about the morality of its use[viii].

There is one other interesting detail. On the viewer’s right, amongst the trees, stands an American who does not have a rifle, but waves what may be a tomahawk[ix] in his right hand while holding an indeterminate object, possibly furry, in his left (Fig 6: Monument to Francis Geary detail). While he is not characterised as a Native American (those who masqueraded as such at this date tended to be naked from the waist up and to stick feathers in their hair[x]) patriots during the War of Independence were accused of scalping[xi], and there might be an implication both that the Americans were acting as savages and that the reason for the non-return of Geary’s body was that he was scalped.

Pevsner (or Nairn) was enchanted by the monument:

‘First-rate; here there is just the right combination of sentiment and ardour. Britannia mourning over a base with portrait medallion, above a splendid delicate relief showing his death in ambush. Often these two parts of a monument do not fit together: here they are combined in a composition as elegant and as tender as an early Mozart symphony, a very rare combination indeed. Unsigned, and it would be difficult to suggest a sculptor: perhaps Van Gelder.’[xii]

No reason is given for the attribution to Peter Mathias Vangelder[xiii], but he did create the c.1782 monument in Westminster Abbey to Major John André (d.1780), another victim of American atrocity during the War of Independence, which incorporates a bas-relief of the Major’s death. The inscription on the Geary monument suggests a date before 1782 when Admiral Geary was made a Baronet[xiv]. The attribution, attractive though it is, is at present unproven, but it is still astonishing that the monument remains unlisted[xv].

There is a postscript. Local tradition in Hunterdon County maintained that the British had recovered Geary’s body, but in 1891 the Hunterdon County Historical Society carried out an excavation at the reputed site of his interment, and found a skeleton, together with uniform buttons from the Queen’s Light Dragoons. As Geary was the only casualty from the engagement the body had to be his[xvi]. In 1907 the Geary family put a stone on the site.

Jean Wilson

[i] William Whitman, “The Church at Great Bookham”, Surrey Archaeological Society Bulletin 448 (December 2014), pp. 3-8, 5. [<https://www.surreyarchaeology.org.uk/sites/default/files/SAS448.pdf>

[ii] <https://e<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalpingn.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambush_of_Geary>

[iii] <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambush_of_Geary>

[iv] < https://americanlongrifles.org/forum/index.php?topic=10252.25>

[v] < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Morgan>

[vi] < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_rifle>

[vii] < https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/revolutionary-war-weapons-the-american-long-rifle/>

[viii] < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Morgan>

[ix] <https://www.furtradetomahawks.com/>

[x] <https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/learn/deep-dives/boston-tea-party/>

[xi] <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalping>

[xii] Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner, revised by Bridget Cherry, The Buildings of England: Surrey (Harmondsworth, 1971), 264.

[xiii] For Vangelder see Ingrid Roscoe, Emma Hardy and M G Sullivan (eds), A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain 1660-1851 (New Haven & London, 2009) 1308-1310.

[xiv] < https://morethannelson.com/officer/sir-francis-geary/>

[xv] < https://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/63638>

[xvi] <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambush_of_Geary>

Fig 1 Map of the Trenton area showing sites mentioned

Fig 1 Map of the Trenton area showing sites mentioned Fig 2 Great Bookham Francis Geary†1776

Fig 2 Great Bookham Francis Geary†1776  Fig 3 Monument to Francis Geary: detail

Fig 3 Monument to Francis Geary: detail Fig 4 Monument to Francis Geary: detail

Fig 4 Monument to Francis Geary: detail Fig 5 Image of Daniel Morgan in rifleman's costume (The magazine of American history with notes and queries (1877) (14781657241))

Fig 5 Image of Daniel Morgan in rifleman's costume (The magazine of American history with notes and queries (1877) (14781657241)) Fig 6 Monument to Francis Geary: detail

Fig 6 Monument to Francis Geary: detail